Pediatric Insight: Passing Leadership Wisdom To The Next Generation

Topic: The Innumerable Costs of an Unsuccessful (FAILED) Search in Academic Pediatrics

Valerie P. Opipari, MD, Bruder Stapleton, MD and Wesley Millican, MBA

There are few responsibilities with more consequences to the leadership of an organization its divisions, departments, school, or hospital/health system than recruiting talent to lead in academic pediatric disciplines. The entire process and level of risk has only increased with time (and increasing burnout and retirement rates and a new generation of physicians less interested in traditional roles). The days of chairs or deans targeting specific candidates through established relationships or known reputation have evolved to highly competitive environments and markets making a search today much more costly, competitive, and complicated. Organizations must now get to “self-aware” prior to initiating a search and be ready to proactively address today’s recruiting environment candidates which are more risk averse and increasingly place higher value on quality of life, family, spouse, partner, and significant other needs. Additionally, it is harder to know who the “up and coming stars” are as fields have greatly diversified, institutions have expanded in both size and number, and new disciplines have emerged that cross traditional departmental/school structures increasingly requiring understanding of interdisciplinary clinical and research needs and opportunities.

No one chair, dean or institute leader can be expected to independently have a grasp on the factors that need to be considered in launching and realizing a successful search and few institutional Human Resource or administrative offices have significant complex faculty search experience or time devoted to this endeavor. Traditional, internally organized search committees, struggle to attract top talent as search processes move far beyond placing advertisements and committee and faculty contacts. Additionally, stakeholders representing the diversity of individuals and groups who will interact with the leader in developing new programs and recruiting additional talent, expect to have a role in the process that chooses their leader. In turn, candidates expect a degree of inclusion, professionalism, transparency, and resource commitments that match the responsibilities and challenges of the position. Anything less only exacerbates the current candidates sense of risk around quality of life and potential failure in the role. While the Covid pandemic resulted in changing many processes for recruitment, most notably zoom interview meetings that reduced on site visits, it has not necessarily impacted the innumerable costs of the search process nor the unintended consequences of a failed search which have only intensified in academic pediatrics. As former directors, chairs, and deans in academic pediatrics we have participated in or led unsuccessful searches. In this report we reflect on this experience and identify 12 critical factors impacted by a failed search with the potential for lasting impact to an organization, its leaders, faculty, and staff and most importantly the children and families they serve along with some reflections on interventions that can reduce the potential of these consequences.

1. FINANCIAL INVESTMENT

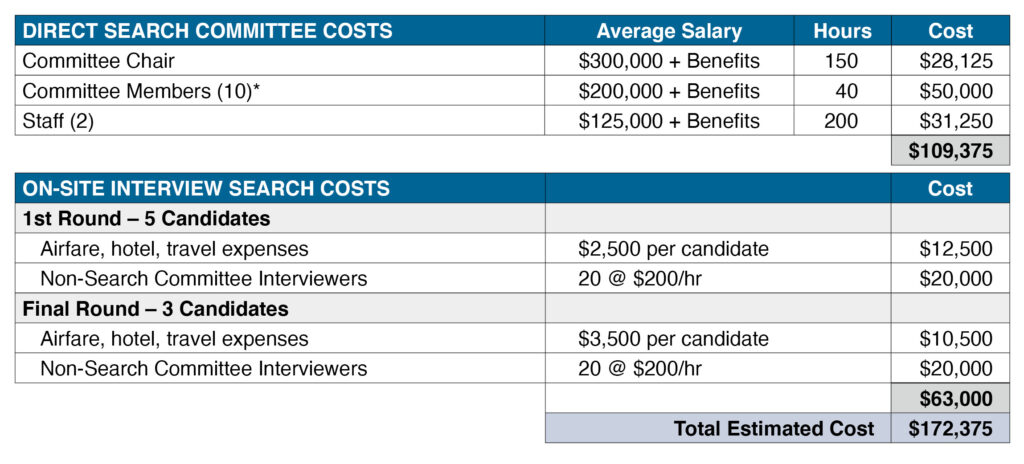

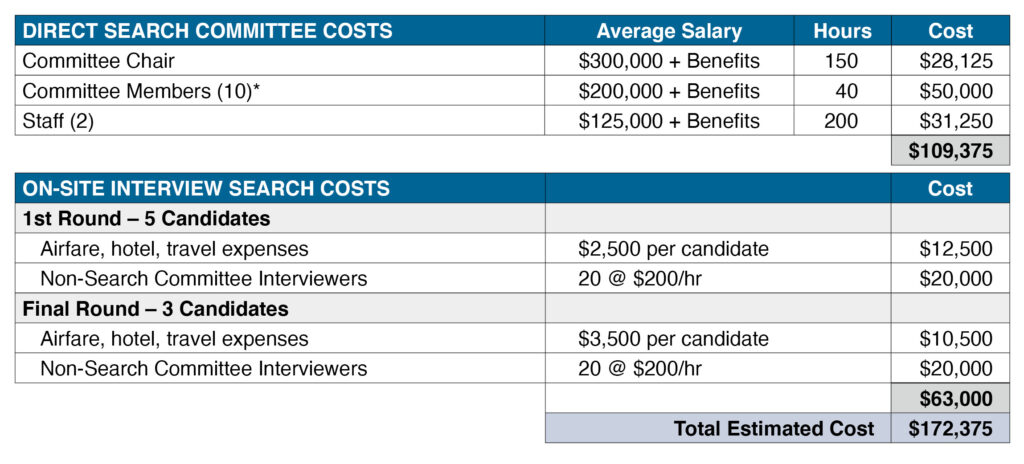

A critical commitment to any search starts with the identification of the faculty and staff who will commit their time and effort to the process, and the establishment and charge to the Search Committee. While the Search Committee Chair and staff assigned to this effort will have the greatest time commitment, all members of the committee, if engaged, will participate in upwards of 40 hours of committee meetings (Charge (1), Planning (2), Candidate Reviews (2-5), 1st round group interviews (3-10), individual candidate interviews (3-10), Ranking Meetings (1-3), and Finalist Selection (1)). Time devoted to these tasks means time taken away from other productive work – clinical, research and educational responsibilities. Often this requires finding colleagues to cover clinics and potentially impacts the timing of grant submissions, finalizing papers, etc. While it is difficult to estimate the costs associated with lost productivity, a conservative estimate of a typical search based on average faculty salaries and estimates of travel/hosting costs for candidates is provided below.

*�Conservatively assuming all search committee faculty have an average salary of $200,000 and benefits at 30%, Non-Search Committee interviewers have an average salary of $150,000 and benefits at 30%, no time for Dean allocated meetings nor meetings with senior leadership, these costs grossly underestimate the real costs for a search with a committee vetting 8-12 and forwarding 3 finalists. Nevertheless, it provides a little insight into the financial commitment an organization makes in launching an external search.

As is evident from this basic estimate of internal search costs there is a significant financial commitment (in this scenario ~$175,000) launching a search in faculty and staff time and financial resources. It should be noted that if an external firm is utilized for the example above, costs will likely exceed $250,000. An unsuccessful search is traumatic for many reasons not the least of which being that most pediatric departments have many potential uses for investments of this magnitude.

2. MORALE

All searches take significant time in planning, executing, and coordinating candidate interviews and visits. Once a search is launched it is public to the entire institutional community and most significantly to the faculty and staff of the division or department for whom the search is launched. During this time there is both excitement and trepidation wondering who the next leader will be and what will be their priorities. A failure to realize a successful search can result in significant damage to the internal culture and morale. Common feelings include: “Why did no candidate want this position? Did the committee work hard on this recruitment? Were resources an issue? Why was I not included in the interviews – I know candidate X and Y – I could have helped? I think they had the wrong people on this committee. I knew this was going to fail!,” etc… The impact of an unsuccessful search can have significant and even lasting damage to the morale of a group and influence future efforts to relaunch the process.

3. LEADERSHIP REPUTATION

Invariably the leader launching the search and often the Committee Chair will be blamed for failing to secure a candidate. It is not uncommon for some to be angry at the time commitment given to an unsuccessful process and lead to questioning the recruiting ability of the leader. People will often jump to conclusions that there was not a true commitment or the resources to be successful were not provided. Faculty or staff who carry these assumptions forward can often derail subsequent attempts to relaunch the search by being apathetic, disinterested or not engaged. “I told you he/she can’t recruit! This is a fundamental role of their position!” “I knew he/she was not willing to provide the needed resources – we just aren’t a priority!”

One of the most significant actions a leader can take with every search conducted is to ensure there is clear, informative, frequent, and timely communication at all steps in the search process. This is particularly critical to searches that are unsuccessful. One of the most significant consequences of poor leadership communication is the negative impact that it has on morale (Critical Factor #2). Every leader will at some point have an unsuccessful search. But those leaders who successfully establish a level of trust through action and effective communication are less likely to experience a negative impact to morale that is permanent following an unsuccessful search.

4. DEPLETED CANDIDATE POOL

An unsuccessful search will mean loss of momentum. This can and is critical in many pediatric disciplines where the pool of candidates is slim and highly competitive. Coming in and out of the recruiting market will raise flags and often leaders will choose to pause and select an interim while they regroup or ‘test’ out an internal candidate they would consider. There can however be costs to settling on an interim or one who is viewed as the ‘wrong’ leader. No one is excited and that often impacts the success of the internal appointee. It can also lead to a sense that the leadership thinks you can “Just put anybody in the position” and some leaders even think this is so – “We know what this division needs – we can drive the needed change with X. I’m not worried.” However, this approach and belief is rarely correct. Importantly, in constrained markets unsuccessful searches often lose out on the ‘top candidates’ and if the interim period is too long or the relaunching of the search is not timely you can also lose your alternative candidates to other institutions. Finally, permanent damage can be done to an interim that is elevated to a position of leadership before they are ready. They can lose confidence and make career decisions that might otherwise have been different by benefiting from additional mentorship before they assume such roles.

When a leader is faced with the need to appoint an interim there are several actions one can take to enhance the likelihood of a successful transition.

- First, consider having the interim take 4-6 weeks to proceed through a complimentary ‘interview process’ whereby they meet and discuss the needs of the position with key institutional leaders and the team they will assume leadership for. Have them review all materials developed for the search and if available, any vision plans or ideas that came from the search candidates.

- Second, make a point to inform the faculty and staff most impacted by the failed search of the outcome first – rather than have them learn the outcome from others. Meet one on one with key stakeholders to similarly ensure they are well informed and support your plans for the interim leadership appointment.

- Third, with the interim leader formalize the appointment with a letter that outlines your shared commitment to their success and the plan they outlined through their interview process.

- Fourth, ensure there are adequate resources aligned to the plan that has been generated. Most important, ensure the letter documents not just the plan for the division but equally important the plan for their leadership development and support as they assume their new role. This should include the defined mentorship/coaching plan and resources to ensure their academic goals are not negatively impacted by assuming this role.

- Fifth, make a clear plan for ongoing one on one meetings with them and the group they are leading to reinforce your commitment to them and their success.

5. RETENTION

Another potential impact of an unsuccessful search is the loss of key stakeholders, faculty and staff who are not willing to wait for new leadership as they are competitive for positions at other institutions. A key strategy for most leaders launching a search is to include these individuals in the search process as members of the committee and/or key stakeholder interviewers. When the search is unsuccessful this can be highly disappointing as hopes for program development or investments are delayed. The saying ‘leadership matters’ is always true. A leader helps to set vision and motivate others to realize their goals and opportunities. Without leadership, creative future driven individuals with opportunity will move to realize their academic goals and potential.

In addition to the critical actions needed to support the interim appointee equally important are the efforts a leader makes to support those key stakeholders that are critical to the success of the division/department. In addition to the strategic communication interventions outlined above a strategy should be put in place to ensure the specific program initiatives and investments critical to the stakeholders are supported. Effectively, these can be put in place with the interim leader appointment letter and shared broadly with the key stakeholders as the investments are initiated. Leadership communication, action and continued relationship building are critical in retaining faculty following an unsuccessful search.

6. EXTERNAL REPUTATION

It does not take time for an unsuccessful search to move from your internal community to the larger academic world. In highly competitive fields this can be viewed as an opportunity to recruit your talent (Critical Factor #5) and an opportunity to retain their own critical talent who may have considered there was strong momentum and opportunity associated with the search at your institution. Highly competitive leaders will have no problem sharing your disappointing news and sadly some may contribute to harming your and the institutions reputation. “Well you heard they had a failed search right – maybe those rumors are real?”

There are only a few things that any leader can control effectively (e.g. those within your control and scope) and efforts to undermine one’s reputation are best met with strong leadership skills and ongoing effective results. Those leaders who have established respected reputations for their communication skills, honesty, advocacy and support of others, their track record building successful programs and supporting the career advancement of others can weather the unfortunate short-term negative impacts of a failed search and potential attempts to undermine reputations. Importantly, taking responsibility for the search results and resisting the temptation to lay blame on circumstances or others, are rarely satisfying and never help. The leader who assumes responsibility and continues to look forward with optimism and integrity will sustain a reputation of strong and effective leadership.

7. STAGNATION AND NEW PROBLEMS

Interim leadership after an unsuccessful search can result in lack of definitive actions and stagnation of a program, division, or department. Whether because of faculty loss, delay in implementing new initiatives or failure to make difficult decisions, awaiting a plan for interim leadership or relaunch of the search, no group is without constant need for decision making and prioritization. Often these pauses or delays result in unexpected problems that require difficult decisions or investments that might otherwise not have occurred or been handled differently if the leader was named and/or soon to be on campus. These new problems and/or their initial solution may result in unintended consequences that impact the reopening of the search. As an example, a clinical lead is named for a three-year term who is ill equipped to oversee the responsibilities of the appointment. This now becomes an issue during the newly launched second search and carries forward to the first term of the named leader.

Several of the strategies already outlined, effective communication, developing an interim plan, skill development of the interim leader etc. can all reduce the stagnation and ineffective decision-making that can occur when a group has no plan nor priorities. If new positions are created every effort should be made to ensure they are time limited, have clear portfolio of expectations/responsibilities and the reporting lines are clear and don’t introduce ambiguity in the organization.

8. POOR INVESTMENTS

In addition to the potential of not handling appointments, promotions, faculty loss etc. because of lack of leadership an unsuccessful search can also be associated with making investments of precious resources haphazardly in the short-term without the benefit of a fresh vision and strategic plan that comes with new leadership and a successful search process defining the future priorities. Sufficient resources to match the leadership/institutional vision is critical to the success of the first leadership term. This coupled with the reality that financial margins from clinical care are increasingly constrained and both could negatively impact the organizations success.

An interim period should never impact the career trajectory of the faculty and staff, nor should it result in a negative impact to the bottom line. As emphasized earlier, the planning and execution of this period are designed to ensure this does not occur. Careful ongoing review of the clinical, research and educational contributions and productivity of the faculty and staff can help to identify issues before they become a problem. These dashboard/critical indicator reviews should occur no less than quarterly and be supplemented by an annual review process that outlines priorities and actions for the year and most importantly, how the faculty and staff are moving forward with their promotions and career goals.

9. INSTABILITY AND LOSS OF COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE

An unsuccessful search has an impact beyond the faculty and staff who will be reporting to the new leader. Division Directors and Chairs have critical roles interacting within the institution and to the external environment. They hold key responsibilities of representation on institutional committees (medical school, hospital, system), they often interact with community organizations and have responsibility for stewarding donor relationships to name but a few. These critical roles if left vacant can negatively impact competitive advantage, loss of market share and failure to realize critical financial resources for ongoing and future investment.

Following an unsuccessful search, the leader must not only create a comprehensive plan at the local level they need to ensure all critical roles and responsibilities are effectively managed at all institutional levels (medical school, hospital, university, community etc.). This may require short-term appointments, delegation of responsibilities and in some instances, taking on additional roles. During such transitions it is critical that a leader prioritize for themselves, the interim leader(s) and key stakeholders how collectively all responsibilities will be addressed and stewarded.

10. SHIFTING ROLES

Related to Critical Factor #9 a failed search can often lead to what is hoped to be short term ‘shifting’ of leadership roles within the hospital, school, or system to those that become permanent and often undermine the responsibilities of the office. As examples, the shifting of Physician-in-Chief roles to the CMO, the creation of clinical and leadership associate positions in clinical and research domains etc… When these shifts are permanently changed, they can be difficult to understand, coordinate and for some candidates may lessen the interest in the position when the search is relaunched.

As noted above, all temporary reassignments of roles should be clearly described, time-limited, and effectively communicated with clear reporting lines. While there can be interest to make permanent structural reporting changes during interim leadership periods they are rarely fully supported and often generate new issues within the organization.

11. DUPLICATIVE EFFORTS

An unsuccessful search means duplication of the initial investment whether one does this again internally or a decision is made to use a search firm. In both instances beyond the financial costs and duplication of effort the community can often be disillusioned and not as enthusiastic as they were with the initial search. This can mean more effort is required to address ‘new problems’ Critical Factor #7 or ‘poor investments’ Critical Factor #8. Many times, with assistance these issues can be quickly identified and resolved or planned for so that the relaunch will be successful. If nothing changes and the issues only get worse rarely will the second search be successful.

12. REALIZING JEDI GOALS

Pediatric academic medicine is in critical need of having faculty and staff that reflect the communities we serve and those that can care for and address the research that will reduce illness and suffering with consideration of human diversity. There are no more sought-after candidates than JEDI candidates in academic pediatrics because of these needs. The advancement and appointment of JEDI candidates demands inclusive search processes that can draw a national pool. An unsuccessful search with JEDI candidates only amplifies each of the issues identified above. Moreover, such a failure will raise internal and external questions as to the commitment to realize any JEDI goal by peers about your and the institutions commitment to inclusion and diversity.

Initiating an inclusive search requires deliberative effort and understanding to remove and reduce the impact of implicit bias and provide standardization to the search process to ensure it is inclusive and advances the diversity of candidates being considered. Several strategies have been successfully employed in academic medicine towards this goal including the use of ‘equity advocates’ (1) and creating high performing teams through mandatory training and standardized evaluation tools and scoring systems (2, 3). Leaders need to be aware of these strategies and consider their implementation with every recruitment they initiate. A formal search offers the opportunity to advance the skills and understanding of faculty and staff in these efforts. Additionally, increasingly schools and departments are formalizing JEDI training on a faculty wide basis to better generalize these principles and importantly, reinforce these concepts and expectations across the organization.

In conclusion, the costs of an unsuccessful search in academic pediatrics can be numerous and each has potential short- and long-term consequences. Beyond financial costs and investments there can be real and significant impact to individual and institutional reputations, issues with retention, failed future recruitment, loss of competitive advantage and momentum, and of utmost importance negative impact to morale and the realization of the aspirations and goals we have in academic pediatrics to impact human health, reduce disease, create new knowledge, and build inclusive caring communities. While this paper focuses on academic pediatrics, the issues we identify are like many fields in academic medicine where markets are constrained and even where they are not. Searching for leadership is time consuming, expensive, competitive, complicated, and hard work. While the negative consequences of an unsuccessful search are very real the benefits of a successful search can be multiplied several fold in the positive and have lasting impact for decades.

References

1. �Chan PS, Gona CM, Naidoo K, Truong KA. Disrupting Bias Without Trainings: The Effect of Equity Advocates on Faculty Search Committees. Innovative Higher Education (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-021-09575-5

2. �Smith, JL, Handley IM, Alexander VZ, Rushing S, Potvin MA. Now Hiring! Empirically Testing a Three-Step Intervention to Increase Faculty

Gender Diversity in STEM. Bioscience (2015) 65: 1084-1087. doi:10.1093/biosci/bvi138

3. �Dossett LA, Mulholland MV, Newman EA. Surgery: The Opportunities and Challenges of Inclusive Recruitment Strategies. Acad Med (2019); 94:1142-1145. Doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002647

About the Authors

Valerie Opipari, MD is a pediatric hematologist/oncologist and Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan School of Medicine and C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. Dr. Opipari has held a number of administrative roles at the University of Michigan including Associate Provost for Faculty Affairs, Associate Chair for Research in the Department of Pediatrics and Chair of the University of Michigan Biomedical Research Council. Most recently, Dr. Opipari served as the chair for the Department of Pediatrics and Communicable Diseases.

Bruder Stapleton, MD is a pediatric nephrologist, Professor Emeritus and Chair Emeritus at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He served as Chair of the Department of Pediatrics as well as Chief Academic Officer and Associate Dean. As a leader, Dr. Stapleton champions a philosophy of teamwork and accountability accompanied with humanistic values. Dr. Stapleton believes that pediatric leaders face many challenges as generational values evolve, resources in the health industry for academic and education missions become limited and disparities challenge trust and collaborations. Many, if not all, of these challenges will be amplified following COVID-19.

Bruder Stapleton, MD is a pediatric nephrologist, Professor Emeritus and Chair Emeritus at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He served as Chair of the Department of Pediatrics as well as Chief Academic Officer and Associate Dean. As a leader, Dr. Stapleton champions a philosophy of teamwork and accountability accompanied with humanistic values. Dr. Stapleton believes that pediatric leaders face many challenges as generational values evolve, resources in the health industry for academic and education missions become limited and disparities challenge trust and collaborations. Many, if not all, of these challenges will be amplified following COVID-19.

Wesley D. Millican, MBA, is CEO and Physician Talent Officer of CareerPhysician, LLC, the nation’s leading provider of comprehensive executive search and leadership development solutions in academic child health. Mr. Millican has 30 years of executive search and leadership development experience having completed more than 600 complex faculty and c-suite leadership assignments. He continues to be a trusted expert in the strategic design of faculty talent solutions for colleges of medicine and their child health partners. Mr. Millican possesses a longstanding passion for the career development of all physicians as exemplified by CareerPhysician’s Launch Your Career Series (LYCS) that serves as a go to career transition resource for program directors and their residents and fellows.

Wesley D. Millican, MBA, is CEO and Physician Talent Officer of CareerPhysician, LLC, the nation’s leading provider of comprehensive executive search and leadership development solutions in academic child health. Mr. Millican has 30 years of executive search and leadership development experience having completed more than 600 complex faculty and c-suite leadership assignments. He continues to be a trusted expert in the strategic design of faculty talent solutions for colleges of medicine and their child health partners. Mr. Millican possesses a longstanding passion for the career development of all physicians as exemplified by CareerPhysician’s Launch Your Career Series (LYCS) that serves as a go to career transition resource for program directors and their residents and fellows.

About the Child Health Advisory Council

The Child Health Advisory Council as a resource of expert insight, wisdom, and consultation for our department of pediatric and children’s hospital clients. Our advisors have been recognized as national thought leaders for their invaluable contributions to their specialty and to the advancement of leadership excellence in academic medicine.

The Child Health Advisory Council is an independent council of former pediatric chairs, chiefs and hospital executives representing more than 100 years of pediatric leadership experience and shared passion for impacting the breadth and depth of academic pediatric leadership. Together, we are committed to empowering physician leaders with the necessary knowledge and perspective to thrive in their leadership endeavors.

Our advisors collaborate with CareerPhysician team to provide expert insight across the leadership continuum, including department reviews, physician search and leadership coaching and mentoring initiatives.

About CareerPhysician

CareerPhysician is the national leader in child health executive search and academic leadership development. The company’s mission is to meaningfully impact the lives of children and their families and the careers of the faculty and leaders who serve them. In collaboration with the Child Health Advisory Council, CareerPhysician provides an innovative suite of executive search and leadership development services that span the full continuum from residents and fellows to senior faculty and leaders. CareerPhysician clients benefit from the company’s 23 years of experience exclusively dedicated to the leadership needs of departments of pediatrics and children’s hospitals.

At the Child Health Advisory Council, we conduct regular roundtable discussions. What topic would you like to see featured in upcoming discussions? Let us know.

Robert S. Sawin, MD

Robert S. Sawin, MD Bruder Stapleton, MD

Bruder Stapleton, MD Christine Gleason, MD

Christine Gleason, MD Craig Hillemeier, MD

Craig Hillemeier, MD Valerie Opipari, MD

Valerie Opipari, MD Bruce Rubin, MEngr, MD, MBA, FRCPC

Bruce Rubin, MEngr, MD, MBA, FRCPC Arnold (Arnie) Strauss, MD

Arnold (Arnie) Strauss, MD Wesley D. Millican, MBA

Wesley D. Millican, MBA

Danielle Laraque-Arena, MD, FAAP

Danielle Laraque-Arena, MD, FAAP Robert S. Sawin, MD

Robert S. Sawin, MD Jon Hayes

Jon Hayes Bruder Stapleton, MD

Bruder Stapleton, MD Arnold (Arnie) Strauss, MD

Arnold (Arnie) Strauss, MD Christine Gleason, MD

Christine Gleason, MD Renée Jenkins, MD, FAAP

Renée Jenkins, MD, FAAP Danielle Laraque-Arena, MD, FAAP

Danielle Laraque-Arena, MD, FAAP